Tony Ardizzone in Conversation

"Stories to Charm the Unborn: An Interview with Tony Ardizzone," by John King and Numsiri C. Kunakemakorn

Copyright © 2000 by Sycamore Review

Volume 12, No. 2, Summer/Fall 2000.

Tony Ardizzone is a Chicago native and the author of six books of fiction, most recently the novel In the Garden of Papa Santuzzu. His writing has received the Flannery O'Connor Award for Short Fiction, the Milkweed National Fiction Prize, the Chicago Foundation for Literature Award for Fiction, the Pushcart Prize, the Virginia Prize for Fiction, two fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, and other honors. He is a professor of English at Indiana University, Bloomington.

John King is currently a PhD student in English at Purdue University. His essays have appeared in Twentieth Century Literature and The Explicator.

Numsiri C. Kunakemakorn is a PhD student in Comparative Literature at Purdue University.

John King and Numsiri C. Kunakemakorn: Your latest book, In the Garden of Papa Santuzzu, often features elements of "folk" stories, but these stories feel different from the folk stories I heard as a child from mass market children's anthologies. Unlike the more wooden and anonymous old world stories I recall, the folk aspects of Papa Santuzzu seem delightfully facile and intimately related to the people telling their stories. Could you describe the importance of these folktales to the telling of the stories in your novel?

Tony Ardizzone: I've always been interested in the stories that people have to tell about themselves, with folktales and myths being one aspect of these stories. Several years ago I had the idea to write a novel about my grandparents, who immigrated to America from Sicily in the early 1900s. I knew at once that I didn't want to write a strictly realistic or factual work, so I looked around for other ways that I might tell their story. As I explored the voices of various characters who ultimately would make up the Girgenti family, I discovered that several of them wouldn't, or couldn't, tell their stories literally. I don't think this is necessarily Sicilian or Italian, but I can remember my grandmother and aunts and uncles telling stories in other-than-literal ways, so the decision to use this method in the novel seemed natural to me.

King and Kunakemakorn: What are some examples of other-than-literal stories?

Ardizzone: Well, my relatives often used metaphorical expressions to explain or describe things. For example, they wouldn't say outright that a woman was pregnant, but that she'd bought a big bass drum, or some other expression, accompanied by a smile or the wink of an eye. They'd refer to others by nicknames that either physically described them or referred to something the person had once done. Someone outside the family wouldn't necessarily be able to follow their references. When you consider that southern Italy, and particularly Sicily, has been colonized and plundered by one nation or another since the beginning of recorded time, a veiled or disguised language system begins to make sense. It's similar, I think, to the region's twisting streets -- sensible to those who live there, a confusing maze to outsiders. So I used this linguistic strategy in In the Garden of Papa Santuzzu because it seemed natural and organic to my characters, and as a writer I found it artistic and interesting. Of course, I worked hard to insure that the novel's various narrators let the outside reader in.

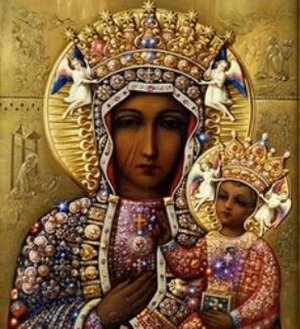

King and Kunakemakorn: The world of the characters in In the Garden of Papa Santuzzu, besides being imaginatively rich with its folk stories, is also a religious one, in a very immediate sense. I think of Anna Girgenti's story "The Black Madonna," in which she relates the visitation of the Madonna with her. I also think of Papa Santuzzu, who will not leave Sicily when the letter comes summoning the rest of the Santuzzu family to America, when he tells his son, "Even if that letter was marked by the hand of God himself...and even if it bore the picture of Jesu's face and three drops of his sacred blood, there are some things here on earth, here on the ground that we walk, in the air that we breathe, in the lives that we live, that are more sacred!" This relationship with religion seems far different from that which we see most often in America. Is there a special connection in this novel between the sense of religion and folk stories?

Ardizzone: Yes, I see them as quite similar rather than as separate or distinct. My sense of Southern Italian beliefs is that they're informed not only by certain tenets of Catholicism but also by the wealth of Greek, Roman, and Arab folklore that makes up the region's culture and history. Religion and folk beliefs exist side by side there, so in my novel I let them merge freely.

King and Kunakemakorn: Who do you consider your literary influences to be?

Ardizzone: Though I'm likely influenced by nearly everything I read, including the work of my students, I'd have to say at the core I've been influenced by James Joyce and William Faulkner. Both work in complex ways with narrative point of view, which above any other narrative technique seems to me to be at the cutting edge of writing fiction.

I've also been influenced by the countless religious stories told to me by the nuns and the Christian Brothers, who for thirteen years taught me in Roman Catholic grammar and high schools. I admire the short stories of Flannery O'Connor and Edna O'Brien, as well as the work of the South-American writers, particularly Mario Vargas Llosa, Gabriel Garcia-Marquez, and Isabel Allende. The ethnic writer part of me has been influenced by the works of Jerre Mangione, Pietro Di Donato, John Fante, and Helen Barolini.

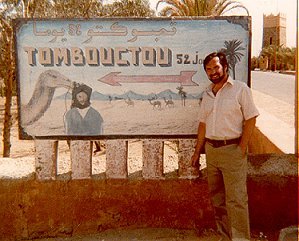

Then, at different stages in my writing life, I allow myself to be influenced by other strains. The Chicago writer side of me has been influenced by James T. Farrell and Nelson Algren. When I wrote Larabi's Ox, I read several books about Islam as well as the Koran and everything by Paul Bowles.

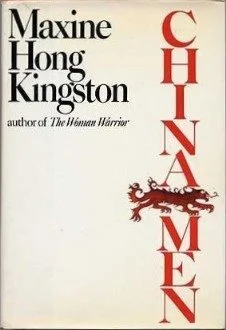

Papa Santuzzu was particularly influenced by Louise Erdrich's writing, especially her first version of Love Medicine, and also by Maxine Hong Kingston's work, particularly China Men. I admire Erdrich's free use of different narrative perspectives, and Hong Kingston's courage to tell the story of her grandfather's coming to America three different ways. Erdrich, at least, owes a lot to Gloria Naylor, whose story collection The Women of Brewster Place helped open audiences, and writers, to interconnected books about communities. Of course, both of these writers owe a great deal to Faulkner and, of course, Sherwood Anderson. I also studied Italo Calvino's marvelous collection of oral folktales, Italian Folktales, which helped me learn form.

King and Kunakemakorn: Your interest, as a writer, in Italian-American life dates back at least to your 1996 collection of short stories entitled Taking It Home: Stories from the Neighborhood, but in In the Garden of Papa Santuzzu the setting is in the turn-of-the-century past. What research did writing this novel require?

Ardizzone: I wrote most of the stories in Taking It Home in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and it was during this time that I began a draft of the book that would eventually become In the Garden of Papa Santuzzu. I spent a year or so on the novel and eventually realized that I just wasn't ready to write it. I wasn't talented or experienced enough at the time to know how to structure the book and shape it into a coherent whole, and since the subject matter was quite dear to me, I didn't want to get it wrong. So I set the book aside.

There are some stories a writer gets to tell only once. I picked the novel up after I'd written my Moroccan book of interconnected stories, Larabi's Ox. By that time I'd traveled in North Africa and written about a foreign place from the perspectives of both Westerners and Moroccans.

Part of the research I put into the writing of Larabi's Ox involved two trips to Morocco over a span of three years. I found a great deal of Moroccan things familiar, and it was then that I began making conscious connections between the cultures of North Africa and Sicily. For example, during my stays there a Moroccan would offer me a particular food, telling me it was quintessentially Moroccan, and it would be something that my grandmother made and taught my aunts how to prepare. More times than not the Sicilian name for the food would be the same as the Moroccan. Several Moroccan beliefs were similar to the ones held by my family. My grandparents emigrated from the North African, or Arab, face of Sicily, which was under Arab rule for nearly two centuries. A friend whose family comes from outside Naples told me that my "discovery" of Sicily was similar to the Arabs' passage up through North Africa. In short, writing about Morocco gave me the confidence to write about Sicily at the turn of the century.

To get back to your main question, I read a great deal of history, including histories assembled by the I.W.W., the Industrial Workers of the World. I studied Ben Morreale's and Jerre Mangione's wonderful book La Storia: Five Centuries of the Italian Experience. I also studied some of the writing by the Sicilian activist Danilo Dolci, whom I salute in the book by giving his surname to the novel's only recurring narrator, Rosa Dolci.

King and Kunakemakorn: How did you initially become interested in writing about Morocco?

Ardizzone: In the mid-1980s I had the opportunity to travel to Morocco and teach at its main school, Mohammed V University in Rabat, as part of an exchange program sponsored by the United States Information Agency. After I returned to the States, I thought I'd write a story about my experiences, so I wrote a slightly autobiographical story titled "The Beggars." Then I wrote a more purely fictional story, then a third. When the third story combined characters from the first two, I realized I had the beginnings of a book. One thing led to the next, including my return to Morocco during the summer of 1988 for further travel and research.

King and Kunakemakorn: When you write in first person, your voices prove remarkably convincing. I recall the adolescent narrator of "Baseball Fever" in Taking It Home who describes his education in biblical stories with a very realistic admixture of religious wonder, childish awe, and adolescent slickness. In In the Garden of Papa Santuzzu, the voices seem equally convincing, and I note that these voices feature an additional quality: they often seem to think in Italian. Cumulatively, how are these narrator-characters different from those in your previous work?

Ardizzone: Well, I'd have to say that the narrator-characters in In the Garden of Papa Santuzzu are more complex since each tells not only an individual story but also a part of the overall family's story. One difference might be that I came to see Papa Santuzzu as a book of voices told by various members of a large family. Over the six years that it took me to write the novel, I came to view the Girgentis as my own family. Or maybe I should say that I came to see myself as one of them. I felt that I constantly had to rise to their level since they knew so much more about the stories they were telling than I did. Some chapters, or voices, required extensive series of drafts, and by this I mean I spent months at a time on a single chapter. The chapter "At the Table of Saint Joseph," which is dually narrated by the twins Rosaria and Livicedda, was perhaps the most challenging piece of fiction I've ever written. I worked on false starts and various drafts of that chapter for nearly eight months.

King and Kunakemakorn: Formally speaking, your modes of storytelling are often intricate. In Larabi's Ox, you tell a series of episodic short stories which follow the experiences of three separate Americans in Morocco who are all introduced in the titular short story. In In the Garden of Papa Santuzzu, the stories of the Girgenti family are told by its various members, are interconnected in terms of subject, and are formally linked by the concept of group storytelling around a campfire, which features the convention of ending each tale with a rhyming couplet which forecasts the next storyteller's story. How has form come to become important in your work, and what is its importance?

Ardizzone: I think all writing, even nonfiction prose, has a form whether or not the writer chooses to acknowledge it. Given this idea, I like to play with a work until it reveals its natural shape and internal structures. My first novel, In the Name of the Father, eventually fell into four parts, which I rather unimaginatively titled "Part One" through "Part Four." My second novel, Heart of the Order, is about the life, death, and rebirth of a baseball player, and after a while I realized its story could be told through nine major chapters, mirroring the nine innings of a baseball game, with an introductory chapter I titled "Batting Practice" and a final, tenth chapter titled "Extra Innings."

I saw the structure of Larabi's Ox as a three-branched tree, beginning with the story of a bus that strikes and kills an ox that has wandered onto a highway, as witnessed by three Americans whose paths begin with this common experience but don't cross again. Their range allowed me to write about the entirety of Morocco rather than limit myself to a primary place or character. The structure also allowed me the chance to have one story in the text talk to another. This is one of the advantages of using a multiple viewpoint. One piece of the text can reconfigure the concerns of another part by adding more details to a given story, changing the details' sequence, contradicting parts of the first story, and so on. This allows a work to present a vision of multiple truths.

The metaphor that helped me structure In the Garden of Papa Santuzzu was a round of stories told one night around a campfire. I imagined a village where at night the people sometimes gather around a large fire, telling stories or singing songs, with the one who begins the first story having the obligation the next dawn to tell the last story as well, thereby completing the circle and tying the knot. This idea helped me know where to begin the work, and how to end it.

King and Kunakemakorn: In Taking It Home, Larabi's Ox, and now in your latest novel In the Garden of Papa Santuzzu, you deal with the effort (and resistance) toward assimilation. What attracts you to the difficulties and emotions surrounding assimilation? Who do you consider your audience to be? Those who have been, or are, assimilating in some sense; those who consider themselves monocultural; or a mixture of the two?

Ardizzone: Assimilation is part of my personal history. Ever since I can remember I've felt the tension between being who I and my family was and who I was supposed to be. I did my best to blend in, but I was constantly reminded of how I didn't fit into the larger group, unless I was willing to reject my ethnic group. When I was in grammar school I envied a kid named Kenneth Webb because he had such a clean, uncomplicated name and was never the target of jokes or ethnic slurs on the playground. He had blond hair and blue eyes. Everybody liked him. I imagined his life to be clean and uncomplicated, too.

I don't view assimilation as a gentle or even desirable process, but rather as something to be resisted if one can. Think of those science-fiction stories in which a powerful race takes over all other species it encounters, morphing them from their native appearance into their own likeness. In In the Garden of Papa Santuzzu, the oldest child, Carla, points out, "As much as I appreciate the abundance and opportunities the New World provides, don't think for a moment that I don't know the price we paid."

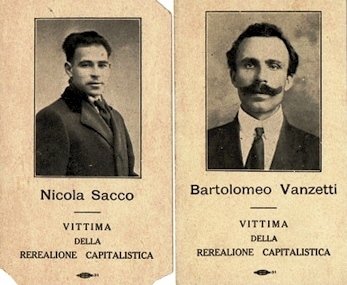

North America's reception of its Italian immigrants was anything but kind. In the South there is a long history of lynching Italians; in fact, our country's largest mass lynching was not of African Americans, as one might think, but of Italians. The unjust executions of Nicola Sacco and Bartolemeo Vanzetti in 1927 attracted world-wide attention. Vanzetti didn't overstate the truth when he said before he died that he was being put to death because he was a radical and because he was Italian. Following the outbreak of the Second World War, hundreds of Italian aliens were interned in camps, like the Japanese. Curfews were imposed, and property was seized. During and after the war, there were active national campaigns to encourage people not to speak Italian, one of the three so-called "languages of the enemy." Employers often encouraged Italian Americans to Americanize their names. Today, the American popular media continues its assault on Italian-American culture by equating being Italian American with outrageous criminality and crude manners.

As for my writing audience, I don't have any one group or another in mind though I do sometimes think of an imaginary reader who shares some of my religious and ethnic background and concerns, or is at least interested in them. For whatever it's worth, throughout all my years of grammar and high school, college and graduate school, I was never once assigned to read any piece of literature written by an Italian American.

Finally, I'd have to say that I write the kinds of books I'd most like ro read. I write books I don't think have yet been written. I write books I think people might still want to read in twenty or thirty or a hundred years. Louise Gluck wrote that true literary writers write for the unborn. I don't disagree.

King and Kunakemakorn: There is a wonderful parallel between the mystical rope that brings "Ia famigghia" to American and the lines of verse at the end of each chapter that connect the stories of all the family members. Both ends of the rope seem rooted to Papa Santuzzu and the ancestral gravesite in Sicily and to Tannu's grave in America. In Carla Girgenti's story, she mentions that America has become less of a foreign "new world' now that they've buried a brother. Could you please talk more about the importance of connection between family members and rootedness, and perhaps why this has become more overtly important in your most recent work than in your previous ones?

Ardizzone: What was most special about writing this book was its connection to my grandparents. I felt that their story and the larger story of the two and a half million immigrants who came to America from Italy was largely untold. Only their stories can connect them to future generations. As they point out, as long as their stories are told and remembered, they can continue to live.

One of the reasons why Papa Santuzzu resists leaving Sicily is that his parents are buried there, and he has buried his wife there. Many Italians came to the New World not with the intention of remaining there but rather with the hope of making some money and bringing it back to their loved ones in Italy, who were literally starving. But in the meantime, in the New World, people die, and death and burial do connect a people to a place.

King and Kunakemakorn: There is a memorable story of three women that test the compassion of family members on their travels from Sicily to America and a hint of their presence toward the end when "the three strangers who watched us from a distance knelt at Tannu's gravesite and grieved." Do they represent the Fates? It seems there is a rich significance in meeting the Fates and being watched over by them on one's journey into the new world. Could you explain this more?

Ardizzone: I placed the three strangers at Tannu's grave in part because they appeared in my imagination as I envisioned and wrote the scene, and in part because they help to make the larger story a sort of folktale in itself, one in which three old women test the mettle of the characters they meet. You know that they approach the family grieving by the grave and ask for something to eat, and are fed. The first part of my answer is the more important. In that particular scene it's snowing, and as I wrote the scene the three old women simply walked toward the gravesite out of the swirling snow. The detail rang true to me, so I kept it. The rest of my answer is a rationalization, formed long after the fact of the writing. As for the significance of the three women, I guess there are any number of myths that might explain them. I'd prefer not to know exactly who or what they represent.

King and Kunakemakorn: There is a certain rawness of emotion and sensory experiences in Larabi's Ox that carries over in a subtle way to In the Garden of Papa Santuzzu. For instance, at the beginning of Larabi's Ox, there are three characters that interact in various ways to their encounter with a dying ox on the side of the road. Their subsequent thoughts and reactions reveal the motivations for their actions and their desires to feel fulfilled or acknowledged in some way. What do you think drives people to look for situations that force them to recognize their potential or limits? Why is it that such an initially frightening experience, like living in a new world, is so alternately maddening and satisfying at the same time?

Ardizzone: I don't think there's any single answer to your question. My three travelers in Larabi's Ox go to Morocco for three different reasons, which take several stories to explain. My Sicilian children of Santuzzu and Adriana travel to La Merica in part because their father told them to and in part because they were starving. In 1985, I went to Morocco to live and teach because the opportunity presented itself and because I thought it was something a writer should do. I mean, to experience. I'm the sort of writer whose aesthetic is based on experience, and what I can't experience I research. As for what might drive people to do this, there are probably as many reasons as there are people. But for me, as a writer, I seek experience because it helps me make better art.

King and Kunakemakorn: In the Garden of Papa Santuzzu deals with union activism and the behind-the-scenes insecurities of being a newcomer fighting with old bastions of power. How do you compare the fears of being indistinguishable as a worker with the fear of becoming culturally undefined as well?

Ardizzone: I'd say both are equally terrorizing, though I'd probably fear the latter more, which may be why I'm more of a writer than an activist. The key here is stories. Cultures live and define themselves by and through the stories they tell about themselves. I see one of my responsibilities as a fiction writer as writing these stories, of giving the not-yet-defined some sense of definition, the voiceless a sense of voice.